Selves Portrait 1: Symbiosis

By Sue Lawton (and Ven Loetz)

When given the luxury of time, reading is one of my favorite activities. And when in the studio, podcasts and audiobooks accompany my process. In recent years, much of what I’ve chosen to read and listen to centers around either science fiction or the natural sciences. If there is one theme that continuously shouts through the noise lately, it’s that biology is messy. Very, very messy. And interconnected. And unpredictable. And ugly. And exquisitely beautiful. Ok, so that’s more than one theme, but you get the idea. Life is complicated.

From a more personal perspective, dealing with autoimmune diseases, neurological differences, and gender identity within myself and family members, the complexity of biology is hard to ignore. With autoimmune disease, it seems like the internal battle lines of “self” vs “not self” get confused, the boundaries always shifting. Our cells are constantly dying and being rebuilt like the ship of Theseus making us not the same physical people we were a decade or so ago and the microbiome makes up more of our body than our own cells. Each organism is, then, not really an individual, but an ecosystem unto itself. Not only am I made up of multiple “selves”, but I am so influenced by the world I inhabit that it is basically an extension of the self. If a global pandemic demonstrates anything, it’s that we’re all breathing each others fog of microorganisms. How we interact with each other matters down to the cellular level.

Details from Selves Portrait 1: Symbiosis

In response to these ideas, I decided to make a series of artworks that examine interconnectedness through some specific species relationships. For the first piece, I chose a merycoidodontidea skull, a mess of lichens, and a series of emerging cicadas as the subject. The merycoidontidea, also known as an oreodont, was a sheep-sized mammal from the Miocene. The skull can be seen in the Cenozoic exhibit on the first floor of the Milwaukee Public Museum. I chose this skull because natural history is personal history and it felt like the right place to start. Back when I was a 14-year-old, I went on a two-week fossil dig through Girl Scouts and this was one of the animals I was digging for. All of the scouts were allowed to bring some fossils home (with permission from the scientists overseeing the dig sites), and a tiny piece of oreodont jaw still sits in my personal collection.

Oreodont skull in MPM (left), Oredodont jaw brought back from Nebraska in 1994 (right)

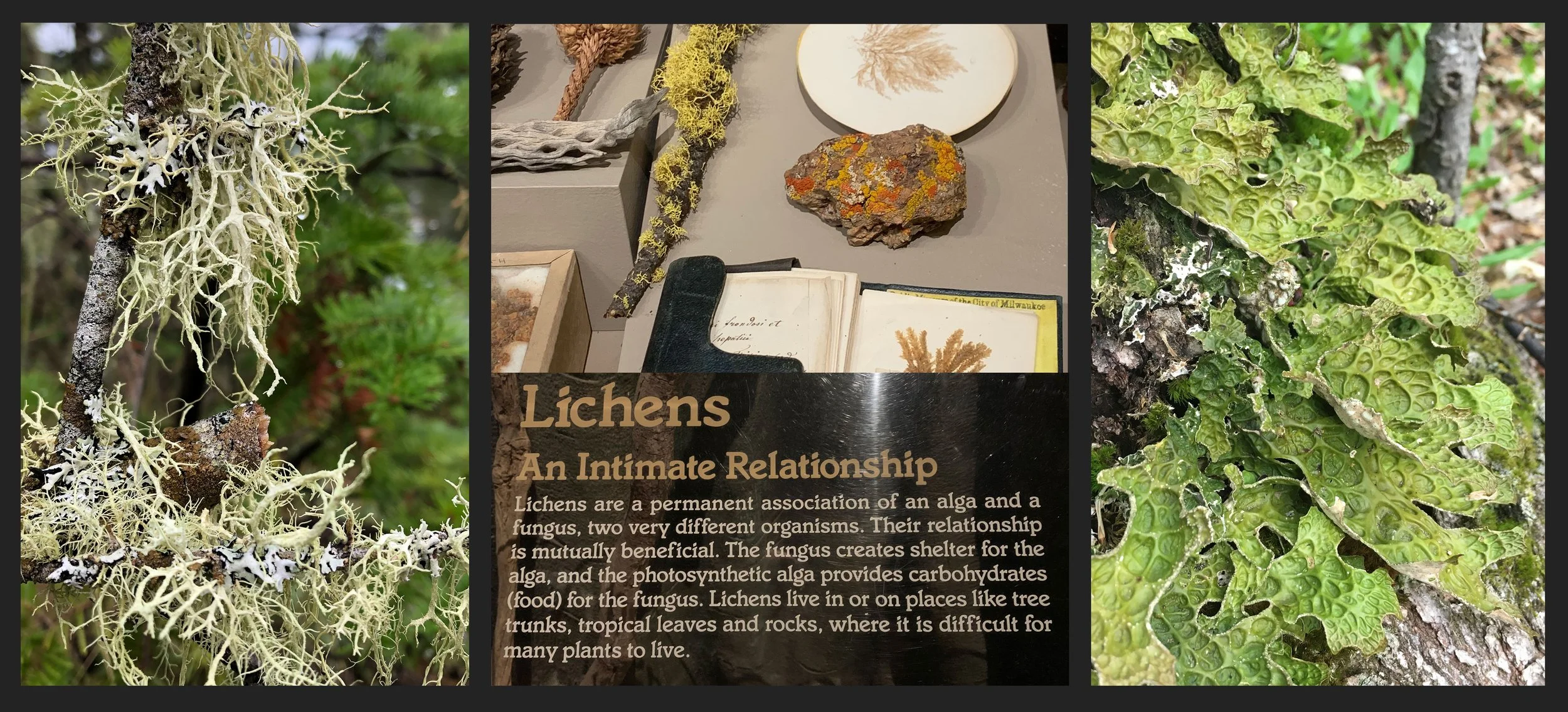

The lichens were chosen because they are composite organisms. They are made up of multiple organisms (usually a fungus, a Cyanobacteria, and a yeast) that work together to form something new. In other words, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. They have an incredible ability to break down materials like wood and rock, take on all kinds of beautiful intricate shapes and colors, and can withstand extreme environments, including the vacuum of space. Photographing lichens has been a passion for many years. You can see lichens in the “A Sense of Wonder” and the rainforest exhibit in MPM. You can also find all sorts of lichen information and resources at waysofenlichenment.net

Photos of lichens found in the wild (left, right) Lichen exhibits in MPM (center)

Cicadas are just fascinating and symbolic on many levels. Cicada nymphs feed on xylem from plant roots underground for 2-17 years (depending on the species). But xylem is so nutrient deficient that the cicadas can’t make essential amino acids to build proteins. This is where it gets weird: they rely on multiple species of bacteria and sometimes a fungi to take the xylem and make essential amino acids for them. This endosymbiotic relationship is so engrained that the bacteria no longer make their own bacterial envelope. The cicadas make cell walls for them. And the bacteria get passed on from mother to offspring when the eggs are laid. The life cycle then involves the nymph digging itself out of the soil to climb up the nearest vertical surface. Then it climbs out of its skin, stretches its wings, and gets ready to mate. You can learn more about them in detail from Big Biology podcast (episode 18: A Bug in the System) which goes deeper into this endosymbiotic relationship. You can find cicadas in many places in the MPM, including “A Sense of Wonder”, the insect exhibit near the butterfly vivarium, and within the rainforest exhibit. And, of course, at the right time in the summer, you can find them outside.

A cicada in MPM’s rainforest exhibit (left), An emerging cicada in our yard (right)

This portrait of sorts, is the first of a series and depicts the balanced relationships of symbiosis. There are many relationships in nature that are not so harmonious, and the next piece will dive into that arena. For now, just appreciate your mitochondria and your gut microbiome. You wouldn’t be you without them.

Books on this topic you may enjoy:

Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake

The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humbolt’s New World by Andrea Wulf